Understanding your vocal tract helps you sing better

Your vocal tract is the main player in making sound. Correct posture and breathing are also necessary, but it’s the anatomical elements from your larynx to your lips that shape the sound you want to create. And because there are many moving parts, I think it’s helpful to look more closely at the major components, to help you understand how they all coordinate.

Your vocal tract is unique to you

The vocal tract is where you create your voice’s resonance – which includes your unique sound’s intensity and timbre. Resonance happens when you control your vocal tract so it alters shape, density, or size, while fast-moving air molecules pass through on your controlled exhale. It’s part of the co-ordination you learn as a singer.

Let’s look at your vocal tract from the outside in.

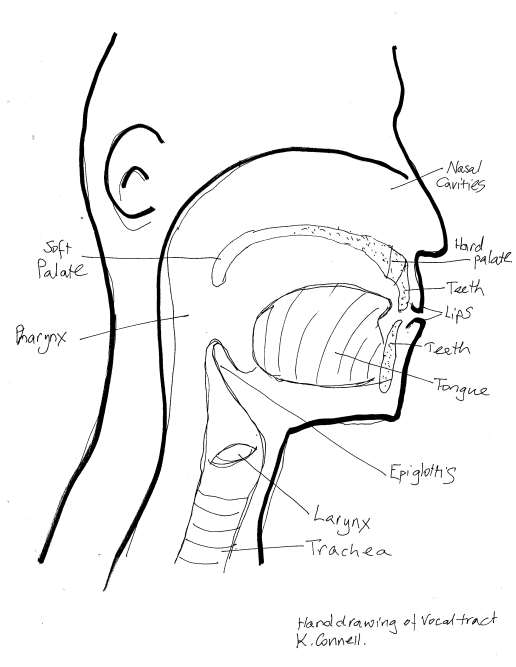

Hand Drawing of Vocal Tract by Kathleen Connell

Lips and oral cavity

Here’s where your vocal tract starts. Your lips open into the oral cavity (mouth), which is bordered by the hard and soft palates at the top and the tongue and jaw below. The side borders include the cheeks, teeth and jaw. The oral cavity houses the articulators you shape to form vowels and consonants. As well as your lips, the articulators include jaw, tongue, soft palate, pharynx and epi larynx – the top part of the larynx. The larynx is where phonation begins, as air flow meets the vocal folds.

The lips are encircled by the orbicularis muscle, which allows them to pucker, stretch, sneer, and frown or pull down. This muscle interacts with other facial muscles to help singers create resonance depending on the tone quality and vowel sound they want.

Tongue

Your tongue is the major shaper of vowels, and helps create resonance, with its ability to move around your mouth and form many shapes. It connects to the hyoid bone at the back and the epiglottis (the leaf-shaped muscle that ensures food and drink go down your esophagus, not your trachea). The tongue also connects to your pharynx and soft palate.

Learning to shape and acknowledge the tongue’s place in your singing is vital. You may be familiar with your tongue’s behaviour when shaping these vowels:

Front vowels: ee, ih, eh, ay, ae – the tongue arches forwards, leaving an open space behind it for sound and breath flow.

Back vowels: oo, oh, ah, aw – the tongue arches back and creates a channel for air to flow through.

Some singers have great flexibility in the tongue, others less so. Misuse of the tongue can upset the balance of singing, and correct adjustments of the tongue need to be finely trained for clear vowels and consonants so your resonance is free and clear.

Soft palate and pharynx

The soft palate is the mucous membrane at the back top of your mouth, and it’s flexible and mobile. Learning to raise the soft palate is a necessary singing skill. Without raising it, you can sound more muffled than resonant.

There is a strong interplay between the tongue and soft palate. If the tongue is depressed down, it will pull the soft palate down, making singing awkward and the sound over-dark. If it’s drawn too high, the tongue can be drawn up and back, producing an unnatural sound quality.

At the rear of your mouth is the pharynx, the largest part of your vocal tract. It is the most important resonator, lined with muscles that allow it to widen, lengthen, narrow, and constrict. It is these constrictor muscles that singers need to release and play with when creating various sounds. The pharynx amplifies the low frequencies in your voice, but if your breath flow is inadequate, it will likely close and you’ll lose the beauty in your tone.

Exercises

To release tongue tension, try this lion yoga exercise:

Drop your jaw and stick your tongue out, curling the tip down to touch your chin.

Place a hand on the side of your neck to make sure you are not tensing the neck muscles.

Keep breathing and hold this position for 30 seconds. Feel the pull on your tongue root.

Pull your tongue back in.

Can you still feel the stretch in your tongue root?

In singing, we need to avoid the large ‘crocodile’ opening of the jaw. At the same time, a minimal opening will not allow resonance through. Try this jaw release exercise in front of a mirror:

Close your molars together.

Place your fingers on your cheeks, near your mouth, and in between your top and bottom teeth. Use the mirror to guide placement.

Leave your fingers there and slowly open your jaw.

Your fingers will slide into the gap between your upper and lower teeth.

That is about the space your need when opening your jaw for an in-breath when singing.

This is one of the oldest and simplest exercises to explore the soft palate:

Hum on mmmm and while humming, pinch your nostrils with thumb and finger to close them.

The air and sound will stop.

Release the nostrils and sing a long aahhh.

Pinch your nostrils again, and the sound will remain the same.

Now try singing a long aahh with a deliberate nasal and unpleasant sound.

Pinch and release your nostrils several times as you sing and see how the sound changes but does not stop.

You find that on a hum, all the air goes through the nose because the soft palate is down.

To strongly shape the lips and lip sounds, use nonsense words on w:

Starting with WOW, try a dull, quiet wow, with little lip movement on a five-note scale.

Keep saying wow, wow, wow, wow, wow as you descend an eight-note scale and become more excited, using huge facial and lip movement as you go.

You don’t need loudness, just intensity of movement.

Now try wubbadubbadoo, well, whoah, wibble wobble.

I hope this overview of your vocal tract, and the exercises, help give you a deeper understanding and mastery of your own singing voice.

Kathleen Connell’s evidence-based singing training helps singers achieve their goals. Browse the in-person or online singing packages, or call 0402 409 106 to enquire.